Breaking the Cycle

By Douglas Lloyd (Dungannon House 2008-2014)

“The bad blood didn’t start with me, it started with my great-grandfather, born in 1904. His father died when he was young, so he didn’t attend school. Forced to dig for gum to help feed the family. Te reo Maori was banned at the Native Schools anyway, and he refused to speak English at home. If kids spoke it, they were punished. The shame of iliteracy—it eats into your bones. He turned into a violent man. Beat his kids. Hated himself. Even treated his mixed-race mokopuna worse than the Māori ones. Two of his sons fought in World War II. They came back carrying ghosts of their own.

My mum was adopted out. She was the second of three children my grandmother gave up because they were born out of wedlock, which was considered a disgrace in their strict Catholic family. She was raised by her auntie, but called her ‘Mum’. She was the youngest of thirteen. Grew up in the Far North. Treated like she was disposable. Then, at 13, she was raped by her sister’s husband. She was blamed. Shipped off to Auckland. Pregnant at 13. Gave birth at 14.

By the time I was born, Mum had four kids by four different men. I was the youngest. We lived in Mount Roskill.

I didn’t realise we were poor. I thought going without food sometimes was normal. Mum would vanish for two to three days at a time, and it would be just me and my brother. There were strangers in and out of the house. If she had people over, we’d get locked in our room.

There was weed. Later, meth.

Eventually, Mum started to unravel. I was about eight when things turned really dark. She became paranoid. Mentally unstable.

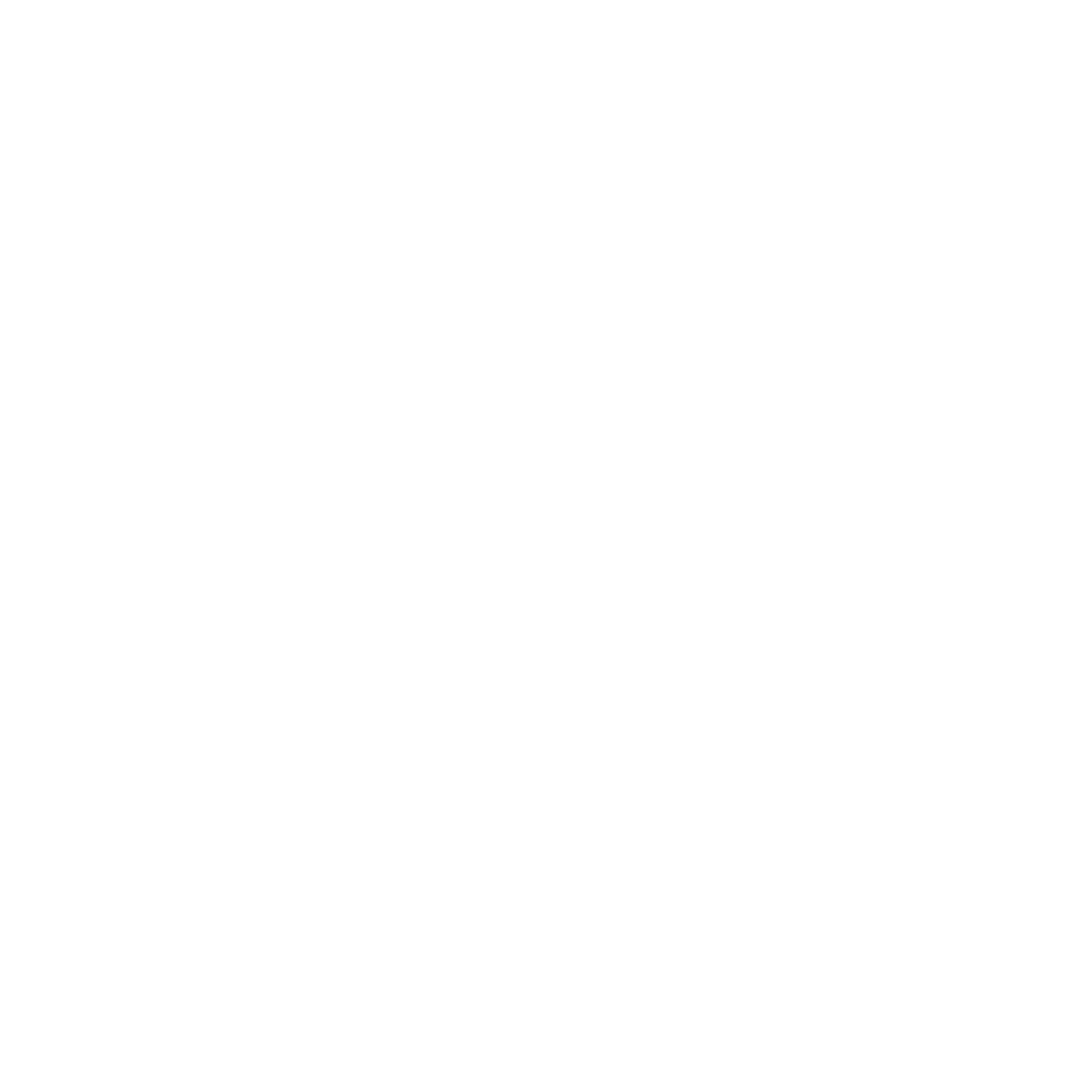

My sister Mia, who was working at the New Zealand Embassy in the U.S., came home to look after my brother and me. We moved away from Mum. About a year later, a neighbour noticed her kitchen light had been on for days so called the police. They found Mum’s body. She’d been dead for four days.

I remember her funeral and someone explaining it to me like this: “You know how a green leaf turns brown?”

She was only 45.

Her family tried to take her body back to the Far North for burial, but she had always said she didn’t want that. So Mia had her cremated. We still have her ashes.

My brother didn’t take it well. He started acting out. Drinking. Smoking. Running off. Mia sent him to board at Mt Albert Grammar. Later, she sent me to Dilworth. I was 11.

That was the first time I ever felt safe.

At Dilworth, I had structure. Belonging. I wasn’t much of a student, but I was good at sport. Rowing. Rugby. Wrestling. That’s where I met my coach—Mrs. Nathan’s husband. He believed in me. Trained me hard.

I started competing internationally. Samoa. Australia. America. I went to the Junior Olympics in China. Came seventh in the world at 63kg. That was huge for me. I felt seen. Respected.

After school, I planned to wrestle in college in the U.S. But I got lost. Thought I was grown, but I wasn’t. Moved to Australia. Got lonely. Started drinking. Fell in with the wrong crowd. Meth followed. Within six months, everything crumbled. I made enemies—some with serious gang connections. It wasn’t safe anymore.

I called my sister and said, “I need help.” She got me a flight home.

I came back to New Zealand in 2016, but I was drifting. Couldn’t hold a job. Couldn’t get out of bed. Tried counselling for the childhood trauma, but I gave up. By 2018, I was at a crossroads. I told myself: Do something. Anything.

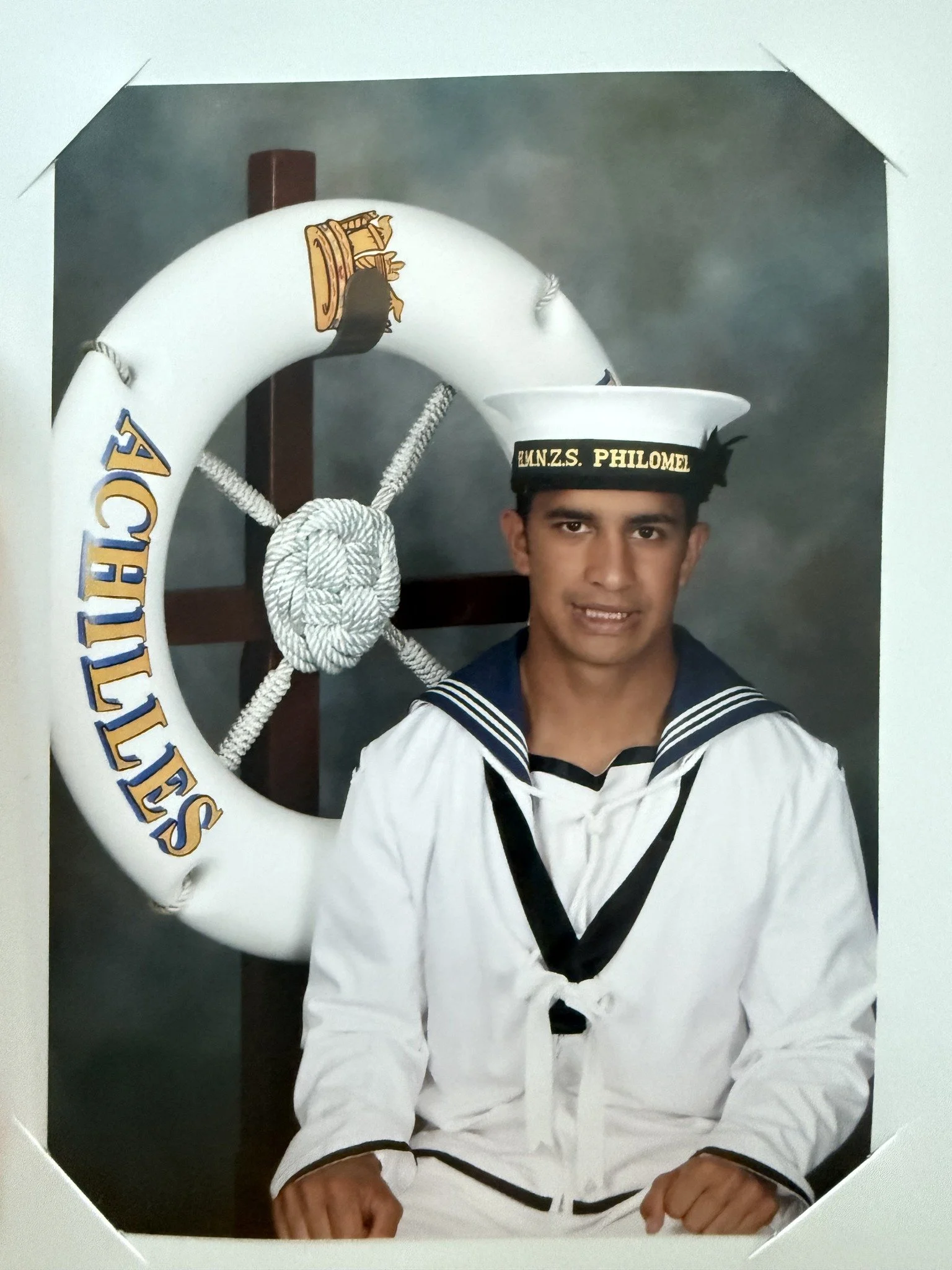

So I applied for the military.

It took two years. During my medical, they found a tumour in my jaw. It wasn’t cancer, but it delayed things again. At that point, I was couch-surfing. No job. No plan. My sister had done everything for me already—she cut ties. I had to figure it out alone. Eventually, I recovered and got into the Navy. Later, I transferred to the Army.

That was the shift.

I found purpose. Routine. Brotherhood. I thrived. Joined the Engineers. Trained for Special Forces. Got injured—but the discipline stayed with me. When I left the Army, I planned to return in six months. In the meantime, I took a job with KiwiRail. Good pay. Steady work. Then I met Audrey. She told me straight: “I’m not raising no army brat.” Gave me a choice.

I chose her.

She believed in me like no one else ever had. Her family is South African Indian—very conservative—but they treat me like one of their own. We got married in February 2024. Now I’m a qualified locomotive engineer. I coach wrestling at Dilworth part-time. I still have Mum’s ashes. She’s with me. And I’m reconnecting with my roots.

I’m Ngāti Kurī—from the Far North. My people have been there since the Arrival. We can recite 30 generations back. When Mum died, we stopped speaking te reo. But I’m learning again. Audrey supports it. My cousins speak it. One day, my kids will speak it too.

I carried all that pain. But I won’t pass it on.

The cycle ends with me.”